America's Camp Meeting Era

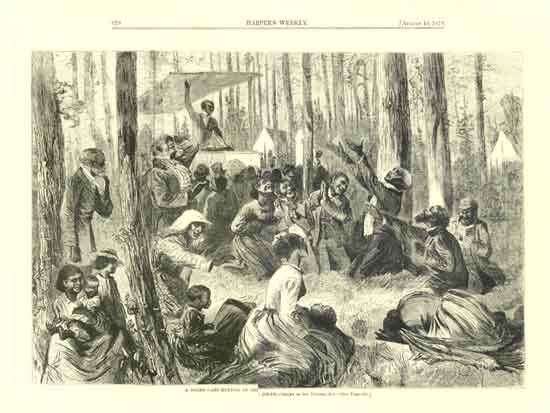

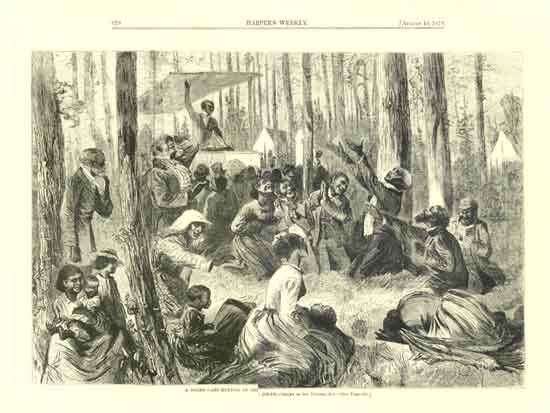

Sol Ettinge, Jr., 'A Negro Camp-Meeting in the South,' engraving, Harper's Weekly , August 10, 1872

America's Camp Meeting Era

Sol Ettinge, Jr., 'A Negro Camp-Meeting in the South,' engraving, Harper's Weekly , August 10, 1872

and its 'NEED' for a taming and tempering influence

Story of America: inebriated on our 'All-American' gospel religion

a spiritual OUTLET for the common folk (before the days of therapy)

Face it, when others called us religious or "enthusiastic" or "that Puritan country" -- it was not always a compliment. And our own bright sons (and daughters) know first hand the flaws and excesses of our unique American religiosity, and have not always applauded.

A favorable appraiser, William C. Spohn, a Roman Catholic moral theologian, takes note of the Puritan heritage that even still permeates the American religious culture, in a largely positive way, he believes. "The American theological tradition has its roots in the Puritan experiment." Spohn delves into the interplay between the enthusiasm of the heart, and the power of reason - as seen through the thought and ministry of Jonathan Edwards in particular. see more

America's frontier religion is so unique as to be, in some sense, unparalleled within Christian theological history. In some respects America's religious landscape offered an unprecedented crucible for religious molting and melting and fusing, with a significant spiritual or spiritualist dimension -- what Spohn calls the "heart" dimension (as opposed to a reason dimension). The only parallel I can find is the somewhat particular example of the Eastern European hasidic movement. This tradition called for an experiential contact with God, something more modern interpreters might call existential religion. Some Hasids phrased it as knowing God by "tasting" Him.

There was often among the Hasidic enthusiasts a suspicion, if not hostility, to erudition and abstruse theological learning -- what they considered pretension and intellectualism.

In America, the two "Great Awakenings" (labels which became handy for later theologians and historians of American religion) took place in colonial times. The First Great Awakening, associated with the name Jonathan Edwards, was largely a New England thing. The Second Great Awakening, associated with other names like George Whitefield, occurred along the what was then America (about the Revolution and Constitution onwards).

Thankfully for our political history, the Founders included a significant intellectual and philosophical component, somewhat removed from the religious populism and social ferment of the frontier gospel movement. Nothing wrong with it, in fact Franklin, Washington and others saw the social benefits of our unique religious side. But the "enthusiasm" of the lower classes (then some ninety percent of America) was a clinching demonstration of the suspicion of direct democracy, the "passions" of the mob, the dangers of "democracy" (small "d"). Our founders opted for filtered democracy, or indirect democracy, guided by "the best" or the most virtuous. That was the ideal, not necessarily what was hammered out at the Philadelphia convention.

Among the common people, the expanding continent offered opportunity. Religion was incidental, I believe, for most of them. It is only in retrospect that we find that America's unique religiosity was to become a defining attribute of the American identity. It became a cohesive force for social "solidarity" or even an impetus towards local "sodality." More enduring churches were formed out of "temporary" revivalist experience. Socialogists refer to the spirit, the gemeinshaft that develops spontaneously, as it were, through a variety of human interaction on a social level.

In America's history, the demarcation line is usually either given as the end of the Revolution, or the year 1800. The nineteenth century through to the Second World War is the period of America's heartland religiosity, the great Bible Belt Americana -- the era of gospelism in American history. This was essentially the frontier movement, and when the frontier closed, so did this movement.

The year 1800 is a tidy one, particularly for the fact of the political and social sea change that occurred with the Jeffersonian Revolution. Though elected by the agrarian "democratic" areas of the West and the South (exclusive of New England and the northeast), Jefferson's advent truly sounded a jubilant fanfare for the common man. His enemies, the "Federalists," were centered in the former Puritan areas, largely, and adhered to the capitalism-building ideals of Hamilton, etc. In religion they regarded themselves the guardians of the old morality, the old values and virtues.

Jefferson and his common folk were suspect. They were the rowdy westerners, the rabble. The Irish flooding into the frontier. Never mind that those Irish had been the "backbone" of Washington's army. Never mind that most of them had been in the New World for almost a generation, sometimes more. Never mind that, for all their rowdy frontier manners, they wanted no more than the chance to better themselves, and chart their own path. True, many of these "Irish" had lost their Calvinism in the vibrant, eroding colliding of diverse faiths amidst the westward flow of people.

In some sense, the sort of religion on the frontier worked almost like a safety valve, emotionally, for the folk who were clearing the forests, settling the west, and establishing the farms with their families. Also, socially, the churches served as a kind of basis for cohesion and (as much as was possible) a unifying force. But religiously or denominationally, the West was a real-life melting pot. The theological "warfare" was intense, but reading about the battles now, they seem almost like fights over trifles.

Some Federalists had predicted the demise of Christian faith, the ruination of the churches with "Mr. Jefferson's Revolution" in 1800. It simply did not happen. In fact, almost the reverse occurred. Churches, especially in the west, actually boomed. For one thing it was the antidote to the drunkenness that seemed to go with the young, restless class of pioneers so often the case.

And in the half-built, under-construction town of Washington city, the widower Jefferson himself -- a Deist or at least independent-minded though he was (known to be "philosophical" in the religion department) -- was observed to attend a range of different churches (and on a regular basis). Admittedly, the churches he picked were mostly the small "outcast" groups which had enthusiastically supported his own "Republicans." (They were the liberals of early America.)

Religious "Awakenings" and revivals and "moves of the spirit" were a necessary and powerful force among the hardy folk of the frontier. From 1800 onward, says Barbara Welter, American religion "entered a process of change whereby it became more domesticated, more emotional, more soft and accomodating -- in a word, more 'feminine'." [quoted in Rosemary Radford Ruether. Women of Spirit. p 207]

Numerous sects seemed to arise of their own volition, almost from the autochthonous soil itself. The "New peoples" of the frontier seemed to crave something social or spiritual. Somethimes faith gave them something intangible, like a lifeline of hope, or meaning. Other times, the very tangible benefits of mutual self-help, and perhaps a neighborliness or gemeineschaft were obvious dividents of the ever-forming new religions.

To the stately and elitist "Old Religions" of the east (and of Europe's palaces and cathedrals), the fertile soil of the Americanist sectarian terrain was suspect, with its ever-multiplying, cross-pollinating, quasi-heretical indifferentism and heedlessness of older forms and theologies. An example was the individualism of an eccentric like Johnny Appleseed.

Johnny Appleseed (ie, John Chapman) was an American pioneer nurseryman who introduced apple trees to large parts of the northwest territories, north of the Ohio river. Wikipedia notes he was an American legend while still alive, largely because of his kind and generous ways, his great leadership in conservation, and the symbolic importance he attributed to apples.

Swedenborgians claim him as a missionary for their New Church, or Swedenborgian Church, so named because it teaches the theological doctrines contained in the writings of Emmanuel Swedenborg. It is said that descendant trees of the originals planted by Johnny Appleseed still live to this day. No name in America is more associated with Apple trees than that of Johnny Appleseed, unless it be the renowned horticulturalists of later days like Luther Burbank and Charles Grandison Patten.

See Johnny Appleseed.

Billy Graham is an icon essential to a country in which, for two centuries now,

religion has been not the opiate -- but the poetry -- of the American people.

[Harold Bloom, dubbed the preeminent literary critic in the world]

Billy Graham - late 1950s

American Evangelist Billy Graham

Some Links

- Anti-Papism in America: the Mother church of all the later break-away churches

- Columbus came, In Jesus'Name: how a devout Italian claimed a new world for God

- Renewal from below : the earthy, democratic Bible thumping religion of our heartland

- The heartland gospel : poor in material comforts, rich in the treasures of faith

- How fanatacism started a war : John Brown and the brushfire revivalism of abolition

- A city set on a hill :: a `New Jerusalem` - is there a divine "destiny" for America?

- Never give up: suffering and endurance [native American saga of hope and triumph]

- Uncanny America :: strange coincidences of America's beginnings (Founding Fathers)

- The European Roots :: medieval antecedents in Age of Faith for our modern world

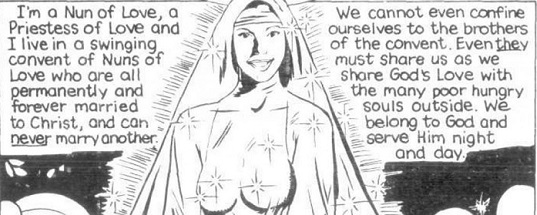

- Anti-Catholic screed :: Papist poison frightens and alarms these True Believers

- Anti-Catholic bigotry joins with anti-immigrant Nativism :: the "Hotel Dieu Nunnery"

- The Last Acceptable Prejudice :: the blame game and artful "recollections"

- A story yet to be told :: "let my people go" (Martin Luther King - the American Moses)

[p215. Liberty of Conscience]

And it still can be found

|

Answering anti-Catholic bigotry

Is all Christianity now suspect?

Just as Christianity itself sprang from Hebraic origins in the Shemitic region of the globe, so also did America's gospel churches grow out of Europe (especially England) -- and out of Catholicism, whether the English or Roman Catholic incarnation of it. So know our forbears. Know our roots. Saint Paul pleaded for a humility on the part of Gentiles (see, he wasn't ALWAYS anti-Jewish -- Jew though he was). Paul reminded gentile Christians they were grafted on to the Jewish olive tree. Gentiles are "adopted" into the Jewish family. What a privilege to call (the Jewish) God our own father, Abba.

So, too, all the breakaway groups, and the groups devolving from those breakaway groups -- must remember our origins. Yes, the Catholic church, with so much more history than any other church, has preserved a record of its sins through the ages. Along with the sins are vast accomplishments as well. Truly, indeed, it is said that the Roman Catholic Church did not merely contribute to western civilization. It BUILT that civilization.

Analogy

Dietrich Bonhoeffer even used such a metaphor, of a Christianity "come of age." His application was not vis-a-vis the Protestant-Catholic schism but rather to a more general Christological or theological re-assessment.

Protestants ask where's the promised Aggiornamiento of Vatican II. Indeed, the brakes which the recent Pope (and John Paul II) have put on reform reminds us of the brakes which the Council of Trent (and Counter Reformation) put on Humanism and that early excitement as if the common people were discovering the Bible for the first time.

I don't want to excuse or condone the leadership's errors through history. Any huge organization takes time to make a turn or change of directions. A huge ship cannot do a turn-around on as small a radius as a small ship.

The absolutism and secrecy of the Church through history looks bad in an age where the democratic spirit predominates. Yet every organization rewards its "saints" and sanctions "heresies" according to organizational standards. This is true in every bureaucracy and every hierarch, from corporations to governments to military. "Obedience" is simply a social virtue for any institution you expect to survive and get things done. Obedience cannot be optional. And disobedience must somehow be discouraged (punished).

|

|

Our history of anti Catholicism

The 'all-American' Bigotry

Susan Jacoby writes, "In the early days of the republic, Protestant suspicion of Catholics was rooted in the knowledge that in every country where Catholicism was the state-established religion, the church had persecuted adherents of other faiths. [Something state Protestantism did as well.] At the time the Constitution was written, the Inquisition was still functioning throughout Catholic Europe. The godless American Constitution protected all religions, but what would Catholics do if they ever obtained a majority through immigration? That question, based on the history of the church iin Europe -- and in regions of the New World colonized by Catholic Europe -- underlay much of the anti-Catholic sentiment of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Of course, anti-Catholic nativism was directed not only at the Catholic religion but at poor immigrants who happened to be Catholic -- first the Irish, then the Slavs and Italians who poured into the country between 1880 and 1924."

"In late-nineteenth century America -- for the first time in Western history since the Christianization of the Roman Empire -- distrust of the Catholic Church's intentions was far more widespread than distaste for religious Judaism." [Freethinkers: a history of American Secularism. p 256-7]

Martha Nussbaum notes part of America's fear of Catholics was based on Europe's track record. "The Roman Catholic hierarchy, in Europe, had played a powerful, and, on the whole, a reactionary role in the struggles for political liberty in 1848 and after." The extreme conservative element controlling Catholic policy took positions that "seemed to undermine a search for greater economic equality, stressing the moral value of the sufferings of the poor, as it might even be morally bad to introduce changes to make [their] lot better."

Additionally, Nussbaum explains that "the Catholic hierarchy on the whole supported the pro-slavery cause during [America's] Civil War, citing Aristotle and St. Paul on their side, increased the suspicion that this religion [Catholic] was linked to political, as well as spiritual, tyranny." [Liberty of Conscience. p216-17]

What are the roots of our human "fear of strangers"? Martha Nussbaum writes, "People love homogeneity and are startled by difference. [Early example, the Quakers with their strange customs, scruples, plain apparel.] Roman Catholics have always seemed strange to Protestants in American history: their rituals, their celibate clergy, their allegiance to the Pope -- all of this has made Americans wonder whether they can be good citizens. The issue of the Pope's role in politics was for a long time used to sideline Catholics in American politics."

[How far we have come! As of late 2010 Protestant America may rightfully pride itself in six Catholics and three Jews on the nine-member Supreme Court.]

Nussbaum tells the Whall case: "On March 7, 1859, ten-year-old Roman Catholic Thomas Whall, a student at Boston's Eliot School, a public school, refused to recite the Protestant version of the Ten Commandments, as required by Massachusetts law. Previously, pupils had chanted the commandments as a group, and Catholic pupils were able to mutter their own version (which omits the Protestant second commandment against the worship of any 'graven image') in a way that escaped notice. On this day, however, teacher Sophia Shepherd had asked each student to recite individually. When Whall refused a second time, a week later, an assistant to the principal said, "Here's a boy that refuses to repeat the Ten Commandments, and I will whip him till he yields if it takes the whole forenoon."

In due course, the little Catholic boy, true to his own upbringing, was horribly whipped by the [Protestant] public school officials. The case went to court.

|

WORTH A GLANCE: The last acceptable prejudice - why does the world hate the Christians Dostoyevsky countered that if God does not exist, anything is possible.

RECOMMENDED READING Constantine's Sword: The Church and the Jews: A History -- by James Carroll

Christianity's legacy of antisemitism is undeniable. Christianity's legacy of suppression of dissent and unorthodox ideas is also undeniable. What is interesting, however, are the ways in which both of these legacies are related and dependent upon each other. Ranging over the entire history of Christianity and the Catholic Church, James Carroll describes how power has been preserved through the suppression of both internal (unorthodox) and external (Jewish) dissent.See Review in Catholic League

Page

by

Robert Shepherd